Bat Boy, Tomatoes, and the Art of Reading

I learned to read in a tomato patch. Ok, well, not exactly in the patch—more like near it, sitting on a rickety folding chair under an aqua-green awning while my mom worked the Parlor Grove roadside market in the river-side hills of rural Kentucky. I can remember it like it was yesterday. It smelled like apples, earth, and the occasional hint of tractor oil. While my dad was miles away in Ohio, putting in long days at General Electric to support the family, my mom would bring me along to her job at “the farm”, where I divided my time between exploring the apple orchards and learning about Bat Boy’s latest FBI chase.

Mom decided early on that I should learn how to read before kindergarten. It was a personal goal for her. A big believer in preparation, she saw literacy as a skill that could be taught during the slow moments between bagging peaches and counting back exact change. She started with the basics: I learned the letters, then simple words, then sentences. I picked it up quickly, which surprised her but also introduced her to a challenge she hadn’t expected: I hated kids’ books. They bored me.

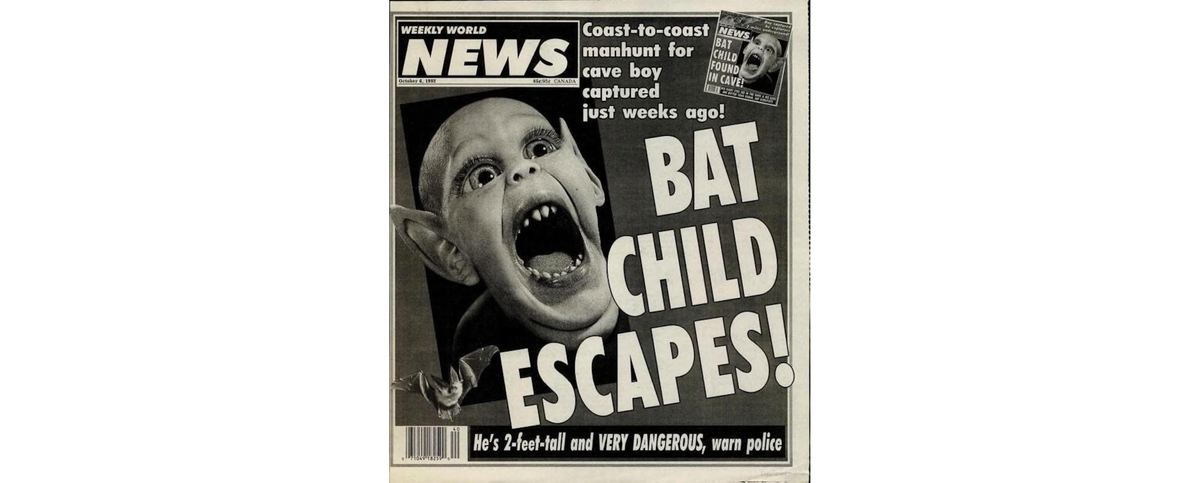

She tried everything—books about friendly bears, adventurous frogs, even one about a caterpillar that couldn’t stop eating. They all bored me to tears. Then one day, we had a breakthrough. “Let me read the paper,” I said, picking up a folded rag someone had mistakingly left one day. By “the paper,” I meant Weekly World News.

To me, it was the greatest publication on Earth. Forget the serious newspaper my mom sometimes read—that thing was a snooze. Weekly World News, with its black-and-white pictures and wild headlines, was where the real action jumped out in bold print. Stories about aliens at Waffle House, Bigfoot’s honeymoon, and Elvis retiring on Mars? Now THAT was journalism. (I would have thought, if I knew what Journalism was...)

At first, Mom hesitated. “This isn’t exactly for kids,” she said, holding it in pinched fingers like it might corrupt me.

“I don’t care,” I replied, pointing to a headline about the Loch Ness Monster. “I want to know about her!”

That was the day my education took a sharp turn. My mom, ever pragmatic, decided, If he wants to learn this way, fine—words are words. So, while customers browsed for tomatoes and green beans, she’d unfold the tabloid and say, “Let’s start with this word: ‘M-E-R-M-A-I-D.’”

Within weeks, I could sound out whole headlines. “Elvis Found Alive!” I'd look up at her in excitement for encouragement. I’d read aloud: “With Martians!” and rock back in my chair. The customers thought it was hilarious. I became known as the weird kid who read the tabloid rags. “Smart kid you’ve got,” they’d say with a slight hint of trepidation as I held court, retelling tall tales about mutant babies and psychic predictions of the apocalypse.

My mom tried to explain the truth. “It’s not real, you know,” she said, pointing at a story about giant killer guinea pigs. “This is just for fun.”

“It’s in the paper,” I argued, convinced. “They wouldn’t print it if it wasn’t true.”

She’d sigh and laugh. “Well, okay then.”

The line between reality and fiction didn’t matter to me. Bat Boy was real. Mermaids were real. The idea that the government could be covering up alien landings seemed utterly plausible. Why wouldn’t they? Adults were sneaky like that.

When I wasn’t reading, I was out in the orchards, my mind buzzing with everything I’d absorbed. The tomato patches became secret laboratories where rogue scientists engineered mutant vegetables. The apple orchards turned into hiding places for Bigfoot, who I was sure lived in the forests that lined the Ohio River. My world expanded with every headline; each story painted a brighter, weirder picture of what might be possible. The world was limitless.

Looking back, those days at Parlor Grove shaped me more than I realized at the time. The market itself was a kaleidoscope of characters: farmers who smelled like diesel and hay, chatty regulars swapping recipes, the weird guy who liked to eat raw green beans, and the occasional eccentric stopping by to tell my mom his theory about pyramids or UFOs or how soda pop could clean the patina off a penny. In between, there were long stretches of quiet where it was just me, Mom, and Weekly World News. I was forged in the fires of the bizarre.

By the time I reached kindergarten, I could read far better than most kids my age. While they were stumbling through primers about dogs and balls, I was sitting at the back of the classroom confused, wondering why we weren’t discussing Bat Boy’s legal troubles or the latest swamp monster sighting.

Eventually, I realized Weekly World News wasn’t reporting actual facts. I don’t remember the exact moment—it was probably a gradual realization—but it didn’t feel like a betrayal. By then, I understood that stories didn’t have to be true to be meaningful. Those tall tales taught me something valuable: the world is as colorful and imaginative as you let it be.

As an adult, I now see those afternoons for what they were: a strange, beautiful mixture of practicality and absurdity. My mom’s goal had been simple—teach me to read—but what she really did was introduce me to storytelling, and the power of words, which can create worlds that don’t exist but feel like they could.

If I close my eyes, I can still picture it: Mom sitting under the shade of the market’s awning, counting change and pointing to a headline while I pieced together the letters. I hear the crunch of her folding chair and the rustle of tomato plants swaying in the breeze. And there I am, five years old, convinced that Bat Boy was out there somewhere, running from government agents and looking for a place to call home.